Over the past decade, the mortgage field services industry has witnessed a series of acquisitions that would make even Wall Street blush. Companies that once competed for the same contracts—creating a marketplace with at least the appearance of fairness—have quietly merged, been bought out, or otherwise subsumed into corporate conglomerates whose primary allegiance is to shareholders, not to the working men and women who keep America’s foreclosure inventory from collapsing into chaos. The recent sale of major property-preservation firms stands as a flashing red light that signals the full corporatization of a trade once grounded in craftsmanship, local knowledge, and fair competition.

What began as a handful of regional property-preservation firms has evolved into an oligopoly where a small cluster of corporations now control the majority of HUD, GSE and private‐investor portfolios. Each acquisition, cloaked in promises of “synergy” and “growth,” has instead resulted in reduced pay for subcontractors, delayed payments for inspectors, and the dismantling of local vendor networks that once formed the backbone of field services. As the IAFST has documented, the consolidation model effectively forces technicians into a race to the bottom under the guise of “compliance” and “vendor alignment.”

The issue is not merely economic; it is structural. When a few corporations dominate an industry, they wield the ability to dictate terms downward through multiple layers of subcontracting. A technician in Pennsylvania or an inspector in Nevada now finds themselves bound by rate sheets written in boardrooms far removed from the field. These companies set the price for labor, determine the penalties for non-performance, and ultimately control who remains in business. The antitrust implications are clear: consolidation creates a vertical choke-hold from the asset owner to the boots on the ground, with each acquisition tightening the grip.

Compounding the problem is the deliberate acquisition of software and data platforms that historically served as neutral intermediaries. When the same entity that sets labor pricing also controls the digital pipeline (work-order flow, reporting, verification), the result is an industry where independent verification of work quality and pay equity has become nearly impossible. Technicians and inspectors no longer control their data; they are data points themselves, monitored, scored, and replaced at will. The IAFST recognizes that this shift transforms independent professional labor into fungible commodity labor.

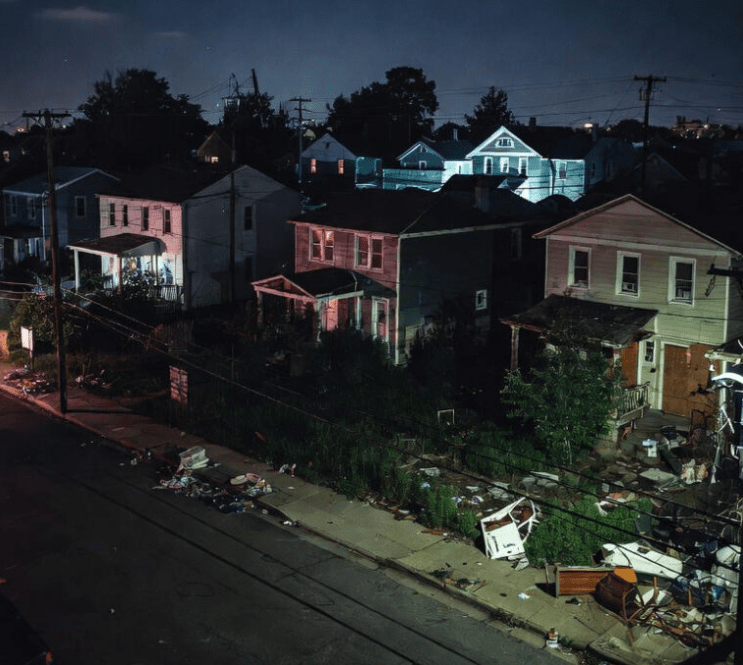

The consolidation also undermines public-policy goals that rely on local engagement. Federal programs intended to stabilize communities—such as HUD conveyance contracts and FEMA/FHA-approved property-preservation work—depend on timely, high-quality work performed by reliable field professionals. When giant firms off-shore decision-making and squeeze labor margins, the result is predictable: missed deadlines, substandard repairs, and escalating blight in neighborhoods that can least afford it. This is not a theoretical concern. Cities across the United States have documented growing backlogs in property maintenance even as the top-tier management companies post record profits.

From a labor-rights perspective, these mergers and acquisitions strip field service technicians and inspectors of the very independence that once defined their profession. The relationship between contractor and subcontractor has eroded into a de-facto employment arrangement without benefits, security, or voice. Rates that once supported small-business viability have been frozen or undercut for more than a decade even as inflation, fuel costs, and materials soared. Every sale of a major company has coincided with a new round of “vendor alignment” – corporate doublespeak for cutting out the middle-class laborers who built this industry from the ground up.